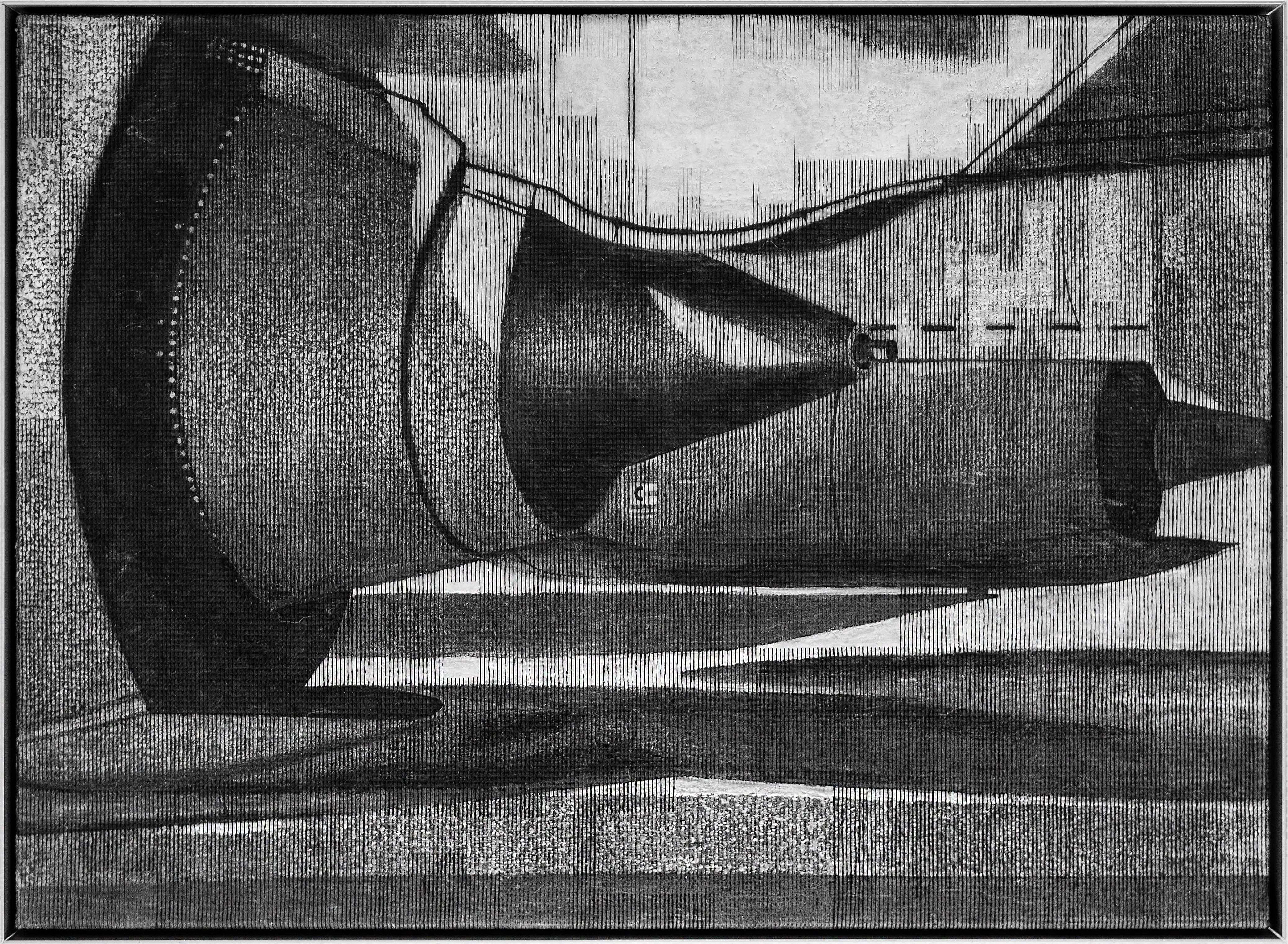

There is a certain comfort in knowing what is real and where things are to have that comfort stripped away can be rapturous, or distressing. Not everyone enjoys the Turrell experience. The air is thick with luminous color that seems to quiver all around you, and it can be difficult to discern which way is up, or out. Stepping into one of his “Ganzfeld” rooms is like falling into a neon cloud. His “Dark Spaces” can require 30 minutes of immersion before you begin to see a swirling blur of color, while some of his rooms are so flooded with light that the effect is instantly overpowering. Other pieces by Turrell are even more disorienting. The room was devoid of boundaries, just an eternity of inky blackness, with the outline of a huge lavender rectangle floating in the distance, and beyond it, the tall plane of green light stretching toward an invisible horizon, where it dissolved into a crimson stripe. The piece that day at Lacma, for example, was one of his “Wedgeworks” series. It is simply too far removed from the language of reality, or for that matter, from reality itself. It can be grating to endure a cocktail party filled with people talking about the “thingness of light” and the “alpha state” of mind - at least until you’ve seen enough Turrell to realize that, without those terms, it would be nearly impossible to discuss his work. Nearly everyone who speaks and writes about Turrell uses the same infernal jargon. Though he is uncommonly eloquent on a host of subjects, from Riemannian geometry to vortex dynamics, he has developed a dense and impenetrable vocabulary to describe his work. This is one of the first things you notice when you spend time around Turrell. It is difficult to say much more about the piece without descending into gibberish. The rush of blood to my head nearly brought me to my knees. It was a looming plane of green light that shimmered like an apparition. Turrell stayed a few steps ahead, muttering directions - “forward now, another step, this way, and turn” - until I rounded the final corner and saw the piece materialize before me.

I walked behind, my hands groping for the walls. “This way,” he said, turning into a dark hallway. We stepped into a dim lobby filled with construction equipment. I followed him inside the building, and we rode an elevator to the second floor. Two hours later, I looked up and saw Turrell standing there with a smile. After the conversation with Govan, I retreated outside and found a bench in the shade to do some reading. We had been spending a lot of time together as he prepared for the shows, and I had followed him to Los Angeles to see the final stages. He tends to dress in dark clothing, like Santa Claus in mourning. Turrell at 70 is a burly man with thick white hair and a snowy beard.

It can take hundreds of man-hours to finish a single room he was erecting 11 at Lacma. Even the drywall must be hung and finished with exacting precision, so that each corner, curve and planar surface is precise to 1/64th of an inch.

#Math illustrations silent install windows#

Windows must be blocked off or painted black to obscure the outside light zigzagging hallways are constructed to isolate rooms and each of the rooms has to be built according to Turrell’s meticulous designs, with hidden pockets to conceal light bulbs and strange protruding corners that confuse the eye. Unlike a show of paintings and sculpture, every piece must be built on site, and even more than with most installation art, his work requires elaborate modifications to the museum itself. As the curator of the Houston exhibition, Alison de Lima Greene, put it, “This is the first time that three museums have mounted exhibitions of this magnitude in conjunction, all devoted to a single artist.” In total, the retrospective takes up 92,000 square feet.Īssembling any Turrell show is a complicated affair. Taken together, the three-museum retrospective is the biggest event in the art world this summer.

As soon as he finished the Lacma pieces, he would race to Texas for another huge installation at the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, and then to Manhattan, where he is opening a show at the Guggenheim next week. The plan had been simple on paper: Turrell would open three major shows inside a month.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)